The body of work on show at the 21st Biennial attests to the multifarious forms in which the idea of imagined communities manifests and makes itself felt in artistic production from the global South. Selected from submissions to an open call, the corpus of this edition stands out for the considerable presence of artists belonging to native indigenous peoples from different countries and numerous works by political activism groups and social movements.

Among the myriad aspects of contemporary experience, these contributions explore the power objects have to evoke history; the conflicts between past and future that shape the present; and the ongoing struggle for access and rights to the land, the driving force behind many social experiments across the global South. Some of the works directly echo the present and its conflicts, especially those that recount experiences of displacement or exile.

In addition to installations, videos, paintings, photographs, and artworks of other natures all gathered together in the 5th-floor exhibition space, the biennial will also feature five video programs (screened at regular intervals in the auditorium on the 6th floor) and a series of performances, activations, and actions involving the audience, including a legal-aid service desk geared towards the trans community; and some political awareness workshops that explore the rich interstice between art and other modes of impacting the world around us.

artists

- #VoteLGBT

- Adrián Balseca

- Ahmad Ghossein

- Alberto Guarani

- Alto Amazonas Audiovisual

- Ana Carvalho

- André Griffo

- Andrea Tonacci

- Aykan Safoğlu

- Brett Graham

- Chameckilerner

- Clara Ianni

- Claudia Martínez Garay

- Dana Awartani

- Ellie Kyungran Heo

- Emo de Medeiros

- Erin Coates

- Ezra Wube

- Federico Lamas

- Gabriela Golder

- George Drivas

- Georges Senga

- Hiwa K

- Hrair Sarkissian

- Isael Maxakali

- Jim Denomie

- Jonathas de Andrade

- Julia Mensch

- Köken Ergun

- Luiz de Abreu

- Marilá Dardot

- Marton Robinson Palmer

- Maya Shurbaji

- Megan-Leigh Heilig

- Mohau Modisakeng

- Mônica Nador

- Movimento de luta nos bairros, vilas e favelas

- Natalia Skobeeva

- Nelson Makengo

- Nidhal Chamekh

- Nilbar Güreş

- No Martins

- Noe Martinez

- Omar Mismar

- Paul Rosero Contreras

- Paulo Mendel

- Roney Freitas

- Rosana Paulino

- Sadik Alfraji

- Tang Kwok Hin

- Teresa Margolles

- Thanh Hoang

- Thierry Oussou

- Tiécoura N'Daou

- Tomaz Klotzel

- Vitor Grunvald

- Ximena Garrido-Lecca

Works

- Voçoroca#VoteLGBT, 2019

- The Skin of LabourAdrián Balseca, 2016

- Al Marhala Al RabiaaAhmad Ghossein, 2015

- Guardiões da memóriaAlberto Guarani, 2018

- About cameras, spirits and occupations: a montage-essay triptychAlto Amazonas Audiovisual, 2018

- Jeguatá: caderno de viagemAna Carvalho, Ariel Kuaray Ortega, Fernando Ancil, Patrícia Para Yxapy, 2018

- Struggle to be heard: Voices of indigenous activistsAndrea Tonacci, 1980

- O golpe, a prisão e outras manobras incompatíveis com a democraciaAndré Griffo, 2018

- Percorrer tempos e ver as mesmas coisasAndré Griffo, 2017

- Uma cor para cada erro cometidoAndré Griffo, 2017

- Off-White TulipsAykan Safoğlu, 2013

- Monument to the property of peace, monument to the property of evilBrett Graham, 2018

- #RESISTAChameckilerner, 2018

- Do figurativismo ao abstracionismoClara Ianni , 2017

- ÑUQA KAUSAKUSAQ QHEPAYKITAPASClaudia Martínez Garay, 2017

- ¡KACHKANIRAQKUN!Claudia Martínez Garay, 2018

- I went away and forgot you. A while ago I remembered. I remembered I’d forgotten you. I was dreaming.Dana Awartani , 2017

- IslandEllie Kyungran Heo, 2015

- Chromatics movement I e movement IIEmo de Medeiros, 2017

- Driving to the ends of the earthErin Coates, 2016

- HidirtinaEzra Wube, 2018

- NOOFederico Lamas, 2018

- Laboratorio de invención social o posibles formas de construcción colectivaGabriela Golder, 2018

- Laboratory of dilemmasGeorge Drivas, 2017

- CETTE MAISON N'EST PAS à VENDRE ET à VENDREGeorges Senga, 2016

- This lemon tastes of appleHiwa K, 2011

- Execution squaresHrair Sarkissian, 2008

- GRINIsael Maxakali, Roney Freitas, 2016

- Off the reservation (Or Minnesota Nice)Jim Denomie, 2012

- Standing RockJim Denomie, 2018

- Procurando JesusJonathas de Andrade, 2013

- La vida en rojoJulia Mensch, 2018

- Binibining promised landKöken Ergun, 2010

- Instalação histórica 1995-2019Luiz de Abreu, 2019

- Livro de Colorir (atentados, 2015)Marilá Dardot, 2018

- No le digas a mi mano derecha lo que hace la izquierdaMarton Robinson Palmer, 2019

- wa akhiran musibaMaya Shurbaji, 2017

- The politics of choice and the possibility of leavingMegan-Leigh Heilig, 2018

- Ga bose gangwe Mohau Modisakeng, 2014

- The Last HarvestMohau Modisakeng, 2019

- Conte isso àqueles que dizem que fomos derrotadosMovimento de luta nos bairros, vilas e favelas, 2018

- Dando bandeiraMônica Nador, 2019

- Imagens de MakwatchaMônica Nador, 2019

- Biographies of objectsNatalia Skobeeva, 2018

- E'ville (ElisabethVille)Nelson Makengo , 2018

- De quoi rêvent les martyrs IINidhal Chamekh, 2013

- Never give upNidhal Chamekh, 2017

- TornNilbar Güreş, 2018

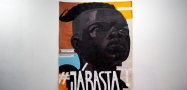

- #JábastaNo Martins, 2019

- Interrupción del sueñoNoe Martinez , 2018

- Schmitt, you and meOmar Mismar, 2017

- Dark paradise: Humans in GalapagosPaul Rosero Contreras, 2018

- DomingoPaulo Mendel, Vitor Grunvald, 2018

- Das avósRosana Paulino, 2019

- I Am the Hunter, I Am the Prey Sadik Alfraji, 2017

- Grandpa TangTang Kwok Hin, 2015

- I call you NancyTang Kwok Hin, 2017

- Tela bordadaTeresa Margolles, 2019

- Nikki's hereThanh Hoang, 2018

- What is left of the sugar cubes?Thierry Oussou, 2019

- Djingareyber Tiécoura N'Daou, 2017

- Ousadia majestade!Tomaz Klotzel, 2018

- Lines of divergenceXimena Garrido-Lecca, 2018

Awards

- The SESC Art Contemporary award#JábastaNo Martins, 2019

- The SESC Art Contemporary awardConte isso àqueles que dizem que fomos derrotadosMovimento de luta nos bairros, vilas e favelas, 2018

- MMCA Residency Changdong Residency prizeSchmitt, you and meOmar Mismar, 2017

- O.F.F. Award [Ostrovsky Family Found]Nikki's hereThanh Hoang, 2018

- Sharjah Art Foundation Residency prizeE'ville (ElisabethVille)Nelson Makengo , 2018

- Honorable mentionGRINIsael Maxakali, Roney Freitas, 2016

- Honorable mentionOff-White TulipsAykan Safoğlu, 2013

- Instituto Sacatar residency prizeI went away and forgot you. A while ago I remembered. I remembered I’d forgotten you. I was dreaming.Dana Awartani , 2017

- State-of-Art Award Electrica Cinema & VídeoLaboratorio de invención social o posibles formas de construcción colectivaGabriela Golder, 2018

Jury members

Trophy design

The trophy the artist Alexandre da Cunha created for the 21st Contemporary Art Biennial Sesc_ Videobrasil dialogues with the idea of national feeling that the North American historian Benedict Anderson, in his essay Imagined Communities, links, among other phenomena, to the demise of the colonial empires. The polished-metal sculpture the prizewinners will receive recreates a coconut with a straw sticking out of it, a sight that is omnipresent on beaches and in the streets of Brazil and Asia. Brought into the context of the Biennial, it reminds us of the informal economies of the Tropics, while provocatively suggesting the phantasmagoria of their paradises-for-rent.

Da Cunha’s coconut reproduces the machete hacks with which the sellers transform the unruly nut into a convenient drinking vessel: a flat slash across the base so that it sits up straight, and the short, crosswise gashes that lop off the cap for the straw hole. For the artist, these are sculptural gestures that speak to the primitive action of transformation and to the sculptor chipping away at a stone. As is recurrent in his work, Da Cunha appropriates the coconut as an involuntary sculpture and so also, in a sense, the vendors as its unwitting sculptors.

Even though operating within a narrow scope of intervention, by recreating the forms and textures of what he calls found sculptures—a coconut, a floor waxer, a one-ton concrete mixer—the artist does much more than merely pluck things from their original contexts. His appropriation, which emphasizes formal issues and sculptural aspects, produces the paradox of evoking ampler themes. Hence his insistence that he is less of a maker than an indicator.

In this case, the disposable straw in the coconut-trophy and the box it comes in, both made from pallet wood, just like the crates used to stack fruit-and-veg at Brazil’s vast municipal markets, end up invoking the legacy of jerry-rigged invention that characterizes postcolonial economies and cultures.

Jury statement

The past, the present and the future appear to be collapsed and condensed.

We are losing our claims on history and our ability to see with clarity. Fascism is on the rise.

We are overloaded with images, communication and the false idea of a global community. We are paralyzed. The present is hijacked in the hands of a few. How do we respond and reclaim the agency now? How do we move on? How do we imagine the future of our communities?

Racism and oppression have become endemic, especially in the targeting of black and indigenous communities. The LGBTQI+ communities are being persecuted. The amazon is burning. We are deprived of our civic rights. This is happening here in Brazil but also all over the world, from Standing Rock to the Maxakali people’s territory, from São Paulo to Tunis. In the 21st Contemporary Art Biennial Sesc_Videobrasil | Imagined Communities, we see that the artworks act as a poetic lens on the critical issues of our times.

Drawing from the ancestral to racial, gender and inequality issues through the works, artists have achieved pertinent results that made our jury process challenging yet exciting. We learned so much from everyone. Saying this, the key points we looked for in the artworks were those that went beyond questioning and the documentary. The awarded works provide answers and proposed possible futures.

We have decided to award and commend two works with the Honorable Mention Award; to Roney de Freitas and Isael Maxakali for their film GRIN, 2016. And Aykan Safoğlu for his video Off-White Tulips, 2013.

The artists Roney de Freitas and Isael Maxakali compose a highly critical and investigative film from important testimonies and archives. Through their own involvement and implication, they are able to portray the complex oppressive structures against the Maxakali communities, since the military dictatorship.

Aykan Safoğlu’s work is a seamless narrative collage of both personal, historical and situational contexts that deal with queer histories. It is very powerful in a subtle and playful way.

As for the Residency Prizes, the first being the Instituto Sacatar Residency Award, we have chosen to award it to artist Dana Awartani for her multimedia installation I Went Away and Forgot You. A While Ago I Remembered. I Remembered I’d Forgotten You. I Was Dreaming, 2017. With a consistent practice that draws from expanding the universal through crafts and contextual specificities, the artist would be able to engage and draw from the experience provided through the residency afforded by this award in Bahia, Brazil.

The second residency award, the MMCA Residency Changdong Residency Award, goes to Omar Mismar on his video Schmitt, You and Me, 2016–2017. Through a very simple strategy that the artist employs, he is able to record a reading of the dimension of subjective power and violence that multiples on the global state of the world today. There is a high level of complicity between artist and subject, which gives new meaning to engagement.

The third residency awarded is the Sharjah Foundation Residency Award, and it goes to Nelson Makengo on his video E’ville, 2018. The artist provides a critical undertaking through video about the postcolonial narratives emanating from Congo. It is looking into conflating the image and material ruins applied to the debris of history and politics. The Sharjah Art Foundation Residency Award would provide the artist with intellectual and infrastructural support for his audiovisual trajectory.

The Ostrovsky Family Fund Award goes to the artist Thanh Hoang for her work Nikki’s Here, 2018. The poetics of this moving image piece incarnates contemporary issues by addressing conditions of labor, intimacy and the resistance against alienation. The use of duration and inventiveness of the artist’s visual and narrative style is outstanding.

From both acquisition awards, the first Sesc Contemporary Art Award goes to the artist No Martins for his series of paintings #JaBasta!, 2019. The remarkable portraits are a statement on affirmation and protestation. The works engage with the historical art of portraiture with an urgent message against racism and inequality. They employ scale, revolutionary gaze and subversive politics and media to create an assertive and powerful call for action.

The second Sesc Contemporary Art Award goes to the collective Movimento de Luta Nos Bairros, Vilas e Favelas on their work Conte isso àqueles que dizem que fomos derrotados, 2018. The video represents collective and meaningful action to social and civic movements that respond to the injustice in Brazil, which largely correspond to the world. It talks to a suspenseful present and desired social future. The active lens becomes one with the action of the community. The result is overwhelming yet exciting.

The final grand prize, the State-of-the-Art Award was unanimously granted by the jury to the artist Gabriela Golder on her seminal four-channel video installation Laboratorio de invención social (O posibles formas de construcción colectiva), 2018. This work is an accumulation of knowledge from organic collectives and cooperatives to create an effective tool for change for workers all over the world. The artist is creating a call for agency on ways to control and organize the economy towards equity. It is a decolonized formula of resistance to the capitalistic and industrial realities and ruins. The installation documents a visual synchronicity in the relationship between humans, machines and the outcomes of their labor to create a unity of voices, actions and lives.

Curator's text 2019

Communitarian Imaginations

GABRIEL BOGOSSIAN, LUISA DUARTE, MIGUEL A. LÓPEZ

Imagined Communities, the book by Benedict Anderson1 from which the 21st Contemporary Art Biennial Sesc_Videobrasil takes its name, is a study about the origins of nationalism and its administrative, cultural, and political expressions. For the author, nations and nationalities are forged by imaginative exercises in which selection and oblivion play just as important a role as the supposedly original (or originary) contents consolidated in national identities. In her introduction to the Brazilian edition of Anderson’s book, Lilia M. Schwarcz takes Brazil as a case in point: in the 19th century, in “full flourish of the empire,” Brazilians saw themselves as inhabiting a European or, “at the very most, indigenous” country, while blacks and mestizos accounted for more than 80 percent of the population.

Corroborating the imaginative character of national identity, Schwarcz points out that miscegenation, long the bane of our intellectuals and men of science, came to be viewed, from the 1930s onwards, as a redemption of sorts, while Afro cultural and religious features, such as capoeira, candomblé, and samba, became the very symbols of Brazilian identity. More contemporaneously, in our market-soaked world, nationalism still musters passions great and small, and its symbols are there for all to see, be it in stadiums and on parade days, or in military conflicts and trade wars in the international arena.

As should be clear by now, imaginary is undoubtedly not the opposite of real. For Anderson, nations can only come to fruition if consistently and systematically imagined and adequately planned. Doing so binds us in a communal and emotional network of meanings. Anderson also argues for the importance of editorial capitalism and reader communities in consolidating notions of nationality; today, information networks are busily creating their own international communities of (fake) news consumers, and so changing the course of the political debate in a host of nations. In such cases, nationalism takes on a toxic aspect and reappears as the subtext to presidential and parliamentary elections in the USA, India, Italy, and Brazil, among countless others, not to mention the Brexit referendum and the debate on global warming. Today, slogan-sewing digital mobs and bots have a real bearing on global governance; the recent refugee crisis in Europe provided a hotbed for nationalist sentiment of the fiercest and most racist kind, and, in this age of the personal soapbox, even some of our little leaders have taken to dispatching via Twitter on these crucial themes.

As the title of the 21st Contemporary Art Biennial Sesc_Videobrasil, Imagined Communities encapsulates an investigation into the presence of certain communitarian concerns in artistic output from the global South. Art, traditionally roped into the imaginative exercise of nationalism in order to supply its founding images, appears here in the reverse role, operating in the shade of grand monuments and within the cracks and crevices of official imaginations. In this sense, the considerable first-time presence of artists and collectives from original and indigenous peoples from different countries and continents confirms the broadened notion of the South adopted in the open call.

Fundamentally State-less nations, Maoris, Guaranis, and Matis are just some of the peoples represented in the exhibition and on the video program in what is a first step toward lending an ear to the vibrant contemporary production emerging out of the indigenous world. Regarding Brazil itself, where the generic image of the Indian was long evoked as a symbol of the nation’s origins and of an identity grounded in a mestizo nationalism, the exhibition of works by indigenous artists endeavors to shed light on their counter-hegemonic poetics and networks of legitimization, at a time when, beyond the bounds of art, indigenous rights and traditional homelands are coming under increasingly violent attack.

The curatorial statement in the open call for the 21st Contemporary Art Biennial Sesc_Videobrasil specified the resurgence of nationalism this century, and native (original and indigenous) communities as the primary subjects of interest. In a process of this size, however, no statement or premise can account for accident. The selection presented is, naturally, much broader and more diverse than the call could have foreseen. One unexpected, but very welcome inclusion was a series of works by activist groups and social movements. In videos, publications, public actions, and services catering to the trans community, they seek to flag ongoing social disputes and broaden the meanings of present-day communities through their insertion on the institutional art scene.

The works by the fifty-five artists participating in the Biennial will be distributed between the Sesc 24 de Maio building and this catalogue. With the selection made, we were able to split the works into five groups in order to highlight the conceptual pillars of this edition. With naturally porous boundaries and constant overlap, these five fields point toward different exercises in communitarian imagination and propose a circuit of meanings loosely reflected in the way the works are laid out in the exhibition space.

The first group on this circuit underscores the capacity certain objects have to evoke history as if they bore within themselves the memories of their former owners or reflected a cross-fertilization of meanings that combines art, national traditions, and mass culture. The conflicts between the past and the future that shape the present gather together the second cluster of works, in which the permanence of tradition (often as trauma) and the idea of the dwelling as a symbolic place of roots and hearth stand out as key themes. Roots that have taken hold in a new land, and conflicts over the occupation and use of the earth, developmental aspects of the social experience in Brazil and throughout much of the South, set the tone for the third cluster of works.

In conjunction with this edition’s video program, the final two nuclei roam beyond the exhibition hall per se to occupy other floors of Sesc 24 de Maio. With Black and LGBTQI+ output featuring strongly, the first of these includes works that resonate more directly with the present and its many conflicts. The final set, consisting of contributions by immigrants from different origins, offers first-hand accounts of displacement and exile, in which the foreign perspective fosters the revision of the past and the horizons of the future. In particular, projects involving the audience participation endeavor to trigger these reflections and so, in tandem with the public programs, expand the Biennial’s zone of impact.

In addition to videos, paintings, installations, and other artworks, this edition also presents a selection of African jewelry wrought in metal belonging to the Universidade de São Paulo’s Museu de Arqueologia e Etnologia (MAE-USP) and a selection of covers of O Snob magazine, a garage journal that circulated in Rio de Janeiro between 1963 and 1969. The rag was a precursor to the LGBTQI+ press in Brazil. The jewelry, produced by the Ashanti, Fon, and Yoruba, was integrated into the MAE-USP collection in the late 1970s and many of the pieces are being exhibited here for the first time. In charge of the selection was the curator Renato Araújo, who has been working with the museum’s collection since 2003. When it came to choosing the covers of O Snob, every single issue of which can be found at the Edgar Leuenroth Archive, at Unicamp, the reference adopted was the work of Rogério Costa, who kindly allowed us access to his vast research findings.

Jewelry and publications, evoking wearers and readers, afford a glimpse of the varied forms our communitarian imagination can assume. In this exhibition, they also underscore the museum-like dimension of a biennial. At a time when our museums are burning down, the presence of collections safeguarded in archives and university museums serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of these institutions to the cultural life of the nation.

Similarly, and operating at the intersections between different fields and knowledge bases, the 21st Biennial’s public programs strive to dialogue with the esprit du jour that guides its curatorial choices. The world that seems to be collapsing all around us, toppled by retrograde winds, does so in reaction to the hard-won victories of recent decades. After a series of advances in mores and micropolitics, accompanied, in the field of art, with a historical revision from a de-colonial perspective—incorporating, in a most decisive way, the ethical/aesthetic landscapes produced by the global South—we are now seeing a sort of counter-revolution, stirred in part by the visibility garnered by a multiplicity of existences hitherto forced into the shadows and silence. This conjuncture goes beyond social and political life: it has the power to jade the imagination, subjectivity, and the unconscious too, and therein lies one of its most challenging features.

Unpacking into a cycle of debates, conversations with artists, guided tours, and performances, the public programs identify and vocalize questions that echo the urgencies of our time. How are we to invent a new political imagination? What meaning can the practices of indigenous peoples and LGBTQI+ groups lend to the idea of community? In a time of colonized subjectivities, what is the role played by the symbolic production of social movements? What micro-political insurrections are chomping at the bit at this time? With these questions, we look to reach out to voices and bodies that are sensitive to the impasses of our age so that we can imagine, invent, share, and exchange new and unheard-of ways of living the future.

The exhibition and public programs are accompanied by two publications that broaden the project’s reflections, documenting the selected works and offering different points of view on imaginary communities and communitarian imaginations. In addition to this catalogue, there will also be a book, scheduled for publication late in 2019, that presents a series of theoretical contributions from the participants on the 21st Biennial’s public programs.

With Videobrasil’s shift to a biennial model, we thought it important that the catalogue should include essayists, thinkers, and authors not directly linked to the exhibition (or to any of its featured artists in particular), but whose contributions bring new depth to the related discussions and offer fresh perspectives on politically relevant issues. The present publication thus becomes a reflexive extension to the Biennial, rather than a simple record of it.

Toward this end, we invited guest authors from a range of geographies and cultural and political contexts: Gladys Tzul Tzul, a Maya K’iche’ activist and sociologist; Erica Moiah James, an art historian and lecturer with the University of Miami; and Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, curator, biotechnologist, and artistic director of SAVVY Contemporary in Berlin. Their essays emphasize distinct forms of forging bonds and communities and of resisting the models of belonging to a nation-state and the nationalist rhetoric that has rebounded so vehemently through ultra-right parties and neoliberal economic policies.

Tzul Tzul embarks from her own personal experience in asking about the implications of thinking politics from a communal perspective, highlighting how the models of social self-regulation in communal indigenous practices make it possible to re-signify the concepts of wealth, property, and use. The author makes clear that, in speaking about the indigenous communal, she is not referring to an identity or an essence, but to a strategy and “a particular form of social relationship” that allows groups to build a shared life and dynamics of autonomy that not only supersede, but openly challenge state government and the politics of representation, which are frequently colonial or paternalistic.

In the second essay, James observes how queer spaces enable us to imagine new territories of existence beyond the normative limits of Caribbean society. Her text reflects on Caribbean Queer Visualities, a recent curatorial project exhibited in Ireland and Scotland that proposes an ambitious panorama of intersections between art and dissident sexualities, proclaiming imagination as an arena for emotional regeneration and social struggle.

The inviability of taking the exhibition on a tour of Caribbean nations, partly due to economic constraints, but mainly because of the prevailing conservatism, reveals the difficulties faced by the local institutions. At the same time, it evinces the power of aesthetics by imagining a Caribbean in which the clamor for self-determination over one’s body has become a form of intergenerational solidarity and taken on a political significance by demanding new alternatives of belonging.

Finally, Ndikung writes about the concept of “deotherization,” a fundamental notion on the program developed in recent years by the Berlin-based cultural center SAVVY Contemporary. As he puts it, “dis-othering starts with the recognition of the acts and processes of othering”; as such, it means fostering processes of resistance to being “otherized,” imagining alternatives for the construction of social identity, and encouraging other forms of filiation and symbolic production. Similarly, reacting to the resurgence of exhibitions that stress determined geographical regions, the author observes how, in many cases, this “tends to become a compensation for a lack of proper engagement with issues of diversity at the level of program, personnel, and public.”

This catalogue also features a special intervention by Marilá Dardot. In recent years, the artist has created a series of coloring-book drawings based on photojournalism images, often representing violence and death. The artist adopts and adapts the best-selling coloring-book format, with its combined pedagogical, entertainment, and even stress-busting functions. In the catalogue, as in the exhibition itself, Dardot’s drawings reproduce photographs (with date and source duly cited) that accompanied Brazilian news stories that broke between 2017 and 2019—a period during which the country took a brusque swing to the right. Thus the artist invites us to establish a relationship with these representations, which visitors to the 21st Biennial will be able to color in for themselves in the exhibition hall.

ASSOCIAÇÃO CULTURAL VIDEOBRASIL. 21st Contemporary Art Biennial Sesc_Videobrasill. From October 9, 2019 to February 2, 2020. p. 48-50. São Paulo, SP, 2019.