The suicide bombers who invented the internet

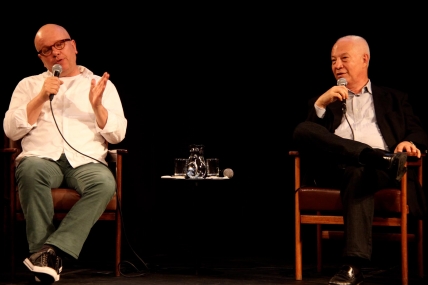

“We used to be suicide bombers and we wanted to revolutionize the television of the millennium.” Marcelo Tas’ address, made during a meeting held yesterday, October 17 at Sesc Pompeia (click here to see the pictures), does not betray the ambition of Olhar Eletrônico, a group that also featured Fernando Meirelles, Marcelo Machado, Paulo Morelli and Beto Salatini and, later on, Dario Vizeu, Renato Barbieri and Toniko Melo. According to him, Olhar Eletrônico wanted to transform not only TV in Brazil, but television language itself, in a broader sense.

The meeting’s mediator, Gabriel Priolli, recalled the context in which Olhar Eletrônico arose, at the time when the TVDO collective was also created: amidst the country’s re-democratization, in the early 80s, college students mobilized themselves, at once looking to break into television and subvert it. This led the group to a standoff. “We established a production company to make videos no one would by,” explained the filmmaker Fernando Meirelles, another participant in the debate. “So Videobrasil was the first space in which for many of us to exhibit and even insert ourselves, from a professional standpoint.” In this regard, Marcelo Tas recalled an effort by Meirelles to sell the group’s products: he even made an edited version of a video by the collective-production company, including cut points for advertisements to be inserted, aiming to conquer the “platinum Venus,” which is how they used to refer to TV Globo.

The veteran at the meeting, the journalist and presenter Goulart de Andrade, helped recollect the period, as he was largely responsible for the professional initiation of both the young people at Olhar Eletrônico and media figures who would eventually become equally prominent, like Mino Carta and Fausto Silva. Fascinated with the group’s outcast verve, Goulart was very bold in introducing those young “video makers”: without warning, he launched them live on his 23ª Hora show, on TV Gazeta. Later on, the group would become his news report crew. “Globo did not know how to deal with that type of programming, so of course I incorporated them into my Comando da Madrugada [TV show],” he says. “I saw creativity in what some dismissed as mere disorder.”

The platinum Venus: love and hate

While Globo invested in visual effects and was more hegemonic than ever, Goulart’s live shows set out to deconstruct that pattern. “As a matter of fact, I wished I could have something more organized, because we had an editing station and it was part of the nature of our work. But it seemed like that was exactly what Goulart wanted. I was impressed with the fact that Goulart seemed to hold sway over that chaos,” said Marcelo Machado, director of the award-wining video “Do outro lado da sua casa,” a landmark piece that gave voice to people who lived on the streets and placed them in the spotlight.

And thus disorder was incorporated into the work of that group. Marcelo Tas recalls, for instance, his coverage of the World Cup in Mexico, 1986, when Nabi, the coach of the Brazilian team, forbade the players from making political statements. Playing the news reporter Ernesto Varela, Tas humorously defied the coach in an interview. “He started getting nervous. Lucas Mendes, then a news reporter for (Globo TV show) Fantástico, turned on his camera and started filming us as we argued. And because Lucas had a satellite, agility, and the entire Rede Globo backing him up, he generated that story and went on air on that same day, a Sunday, on Fantástico. My own report took two or three days to air – we edited it and whatnot. But, by the time my interview went on air, we had a huge repercussion; the appearance on Fantástico was like a teaser," he says.

Other times

Ernesto Varela “was born,” created by the Olhar Eletrônico collective, and was incorporated by by Goulart de Andrade into his show. He, the character, is a sort of icon of the type of journalism they pursued, and which set out to defy with humor, to criticize politicians, “having Maluf as the main target. We were out to get him. But not even Interpol has succeeded, so...,” Marcelo Tas quips.

A story that is well representative of the freedom with which they created their own language at that time was told by Fernando Meirelles: in order to make their newscast presentation more fun, they had the reporter speak standing by a car, which was supposedly broken down, rendering him unable to arrive at the site of the news story. The joke lasted through the two hours of the program, and turned out very expensive: they failed to remember that the carmaker was the main advertiser, and withdrew its sponsorship.

At the same time, Olhar Eletrônico – at times dubbed a production company, at others a collective, and at others a company during yesterday’s meeting – had a certain academic interest that, Machado believes, verged on pretension. Through the initiative of Dario Vizeu, who has been called “the group’s mentor, curator, and medicine man,” they used to promote study groups that would receive the likes of Antunes Filho, Walter Clark, Olgária Mattos and Mino Carta. To Gabriel Priolli, this was one of Olhar’s differentials in relation to TVDO, another collective/video production company of that time: Olhar was partly dedicated to theoretical research.

The internet and other inventions

A completely uncommon initiative sums up the freshness of that movement. When they were supposed to deliver to Goulart de Andrade the last program to be show, they filmed a large fish tank. That was it. For two hours. And the program did go on air, to the sound of a suggestive voice, with musical backing by Brian Eno, saying things like “are you feeling lonely? Call this number” – the number was for Meirelles’ mother’s home, where they had convened. The caller would leave their name and number, which were passed on to the next caller. “We invented the internet,” Marcelo Tas teases.

But there were other inventions as well. Responding to a question from Gabriel Priolli, Fernando Meirelles says a few features of current TV newscasts are a heritage of the way they used to create their work back in the 80s: editing statements without hiding the cuts, using detail frames (a regular practice up until then), using the city landscape as a setting, and having the presenter walk around the newsroom during a newscast are some of them.

Click here to read about the debate held in the previous day, featuring Zé Celso, Tadeu Jungle, Pedro Vieira and Walter Silveira. The meetings on October 16 and 17 were the first Public Programs activities of the 18th Contemporary Art Festival Sesc_Videbrasil.

Subscribe to our newsletter in the box on the left to remain up-to-date with our latest news.

Go to our Facebook page for pictures of the event.

Channel VB: Watch statements form Fernando Meirelles, Marcelo Tas, Marcelo Machado and Goulart de Andrade, as they discuss their early work in video language, and the space created by Videobrasil in the country since the 1980s.